07 :: Big-Wye Yoga

Prior to attending yoga Teacher Training, I was preparing to share all the yoga-things that I was doing. It seemed like the thing to do as peers in my community were doing the same. After Teacher Training, I swiftly realized that I didn’t know much about Yoga at all. Furthermore, I was now aware of the fact that much of what I have been experiencing was not unique to me and that others were much more eloquent and qualified to express the hidden wisdom found in a Yogic practice. Such insights have been around for centuries, if not for millennia. What I have been experiencing is that my broken body is continuing to heal – a product derived from practicing yoga. What I have learned is that this is not the Ultimate Goal of Yoga.

Yoga is the stilling of the changing states of the mind.

1.2 The Yoga Sutras of Patañjali

I learned this aphorism at Raja Yoga Academy. At the time, I was more concerned with completing the appropriate boxes to gain my teaching certification than with exploring the deeper meaning and metaphysics of Yoga. It did, nonetheless, introduce me to Patañjali, the author of Yoga Sutras which has been an invaluable resource in understanding what Yoga is. His text is by no means the ultimate authority (the Gita alone discusses three types what is to say about the Puranas). It has also taken me three years to digest its contents and I continue to go back to the sutras, and accompanying commentaries, to gain a deeper and more complete understanding.

While Patañjali is known as the Father of Yoga, he is not its inventor According to yogic lore, that credit belongs to Shiva, the first yogi, and the originator of Yoga. It is said that Shiva passed on the seven aspects of Yoga to seven great sages who were entrusted to pass this knowledge on. Seals and fossils found in the Indus Saraswati Valley suggest that practitioners of Yoga were present in ancient India, while literary works that make mention of Yoga were seen in the pre-Vedic period, 2700 B.C.E.

In his time, Patañjali saw that Yoga was becoming too diversified and complex. With nearly 200 aphorisms divided into four chapters: Meditative Absorption, Practice, Mystic Powers, and Absolute Independence, Patañjali codified the knowledge of the time into a singular system. Sometime between 500 B.C.E. and 800 C.E., the commentaries of Vyasa’s on the Yoga Sutras emerge. Some scholars hold that the author of the Yoga Sutras and Vyasa’s commentaries, the Yogabhyasa, are one and the same, while other hold that they were two different individuals. Regardless, the sutras serve as a collection of cryptic aphorisms on Yoga, whereas the commentaries serve to give insight and expand on the understanding of the concise collection of words. Together they serve as a map, guiding an aspiring-yogi to Yoga’s ultimate goal: samadhi; a state of meditative consciousness.

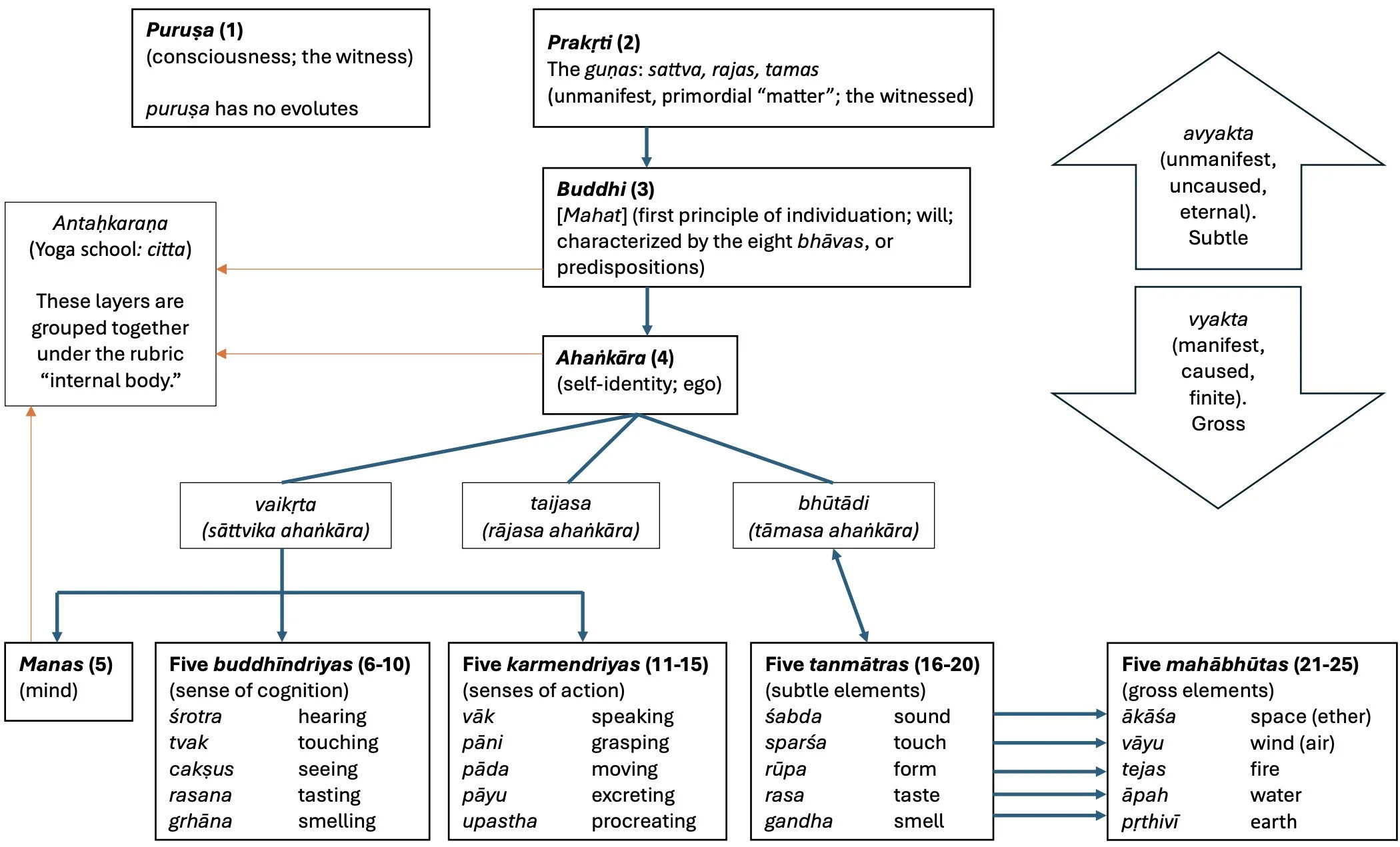

To understand what meditative consciousness is, we need to first understand the school of Yoga’s view on reality and existence. Yoga metaphysics posits that fundamental reality is comprised of two parts, consciousness and matter; the seer and the seen; the witness and the witness; purusa and prakrti. Two ontological categories that are completely distinct from each other.

Matter, in this system, are not only the things we experience through our senses, but it also includes our thoughts, emotions, and mind as well. In short, everything in the material world. But if our mind is contained in the category of matter, wouldn’t that include consciousness? In short, no. The mind, in this system, is a pseudo-consciousness, an illusion.

Pure Consciousness, on the other side is separate and discrete from matter. This consciousness is like a lamp, an oft used metaphor, which illuminates matter, making it known. It is the entity that witnesses the material world. When the material mind experiences this illumination, the mind thinks that it itself is doing the seeing, but the mind is, in actuality, the thing being seen.

In Patañjali’s system he proposes that this ignorance, the misidentification of between consciousness and matter, is the root cause of embodied existence. By cultivating the ability to meditate, that is, to exert control over one’s mind, an aspirant can discriminate between the seer and the seen and is able to experience reality as pure consciousness. This is the state of samadhi, meditative consciousness.

But it is not enough to just know about these two distinct, ontological categories, one must personally experience it! Yoga, if I, and so many others may be so bold as to say, is predicated on direct experience. The Yoga school is very clear about its epistemology, the investigation of what distinguishes justified belief from opinion, that is, the theory of knowledge. Patañjali lists three methods: sense perception, inference, and verbal testimony, that are accepted by the school of Yoga. It is important to note that in the sutra tradition, items that lead a list hold more importance than the items that follow. In this case, inference, and verbal testimony are dependent on sense perception. One must have experienced it before they can deduce it or talk about it. When I think about Yoga epistemology, I cannot help but to think of the old idiom: The proof of the pudding is in the eating.

The Twenty Five Tattvas of Classical Sankhya

While Yoga may ask an aspirant to start with some faith-equity, it ultimately requires an aspirant to verify any claims to truth directly through their own exploration and practice. Verbal testimony may inform us of the path, and inference may help to remove any doubt about the path, but sooner or later we must walk on the path if we wish to attain its goal. There is no substitution for sustained practice say the classical commentators, aside from divine intervention.

In chapter 1, Patañjali identifies two requirements needed to restrain the changing states of the mind: practice, and dispassion. He defines practice as the effort to concentrate the mind and dispassion as the absence of craving for sense objects. This is a tall order for one who has not yet cultivated the ability to control their mind. As such, in chapter 2 Patanjali offers a more accessible type of Yoga: Kriya-Yoga. This consists of discipline, study, and dedication to (a personal) God, which are identified as practices that are conducive to eliminating the obstacles to samadhi. Practice, dispassion, discipline, study and dedication to God are re-presented within Patañjali’s Eight Limbs of Yoga, Astanga-Yoga. It is interesting to note that in the Eight Limbs, yoga postures (asana), is the third limb. This infers that is it not the end-goal and indicates that it is not more important than the first two limbs: moral imperatives, yamas, or virtuous habits and observances, niyamas. The foremost yama, the first of the first so to say, is non-violence, ahimsa.

Yoga is… predicated on direct experience.

Ahimsa is non-negotiable. To practice Yoga means that one must practice non-violence. Vyasa asserts that all living beings give up their enmity in the presence of one who is established in non-violence so it should be expected of an aspirant to expose and root out any perverse thoughts of violence.

In the West, yoga is predominantly presented and practiced as an exercise for physical fitness. Surely, westerners are more familiar with Downward Dog than they are with the 25 Tattvas of Classical Sankhya, the metaphysical system used by the Yoga school. If westerners are not conjuring up images of practitioners contorting their bodies into different shapes, then, perhaps, they are envisioning an ascetic sitting in lotus-pose whilst meditating when they hear the term “yoga”, or “yogi.” I certainly was under the assumption that the postures and an ascetic lifestyle was Yoga, but while these are certainly a part of Yogic practice, it is just a part of a greater whole.

Bikram yoga (26&2; Original Hot Yoga) is a posture-based class and the merit of its practice leads to a healthier and more functional body, but what differentiates a Bikram yoga class, from, for example, from practicing calisthenics? In a Bikram class, a practitioner has the potential to practice what I like to call, big-wye-Yoga, in contrast to small-wye-yoga. Using this nomenclature, yoga is akin to calisthenics, whereas Yoga is working toward samadhi, meditative concentration. While on the surface, Bikram yoga is taught as yoga, if a practitioner is committed to the practice, they may soon find themselves practicing Yoga. At least, this has been my experience in my Yogic journey.

“In a Bikram class, a practitioner has the potential to practice... big-wye-Yoga”

You see, while Bikram’s sequence is comprised of 26 postures and 2 breathing exercises, the secret sauce lies in the room in which the class takes place and the effort one brings into the room. It is hot, humid, and you are surrounded by mirrors and fellow practitioners. It is designed discomfort. Whether realized or not, you will be presented with your physical dysfunctions as you move through the postures. The monkey mind, restless and distracted, will try to seek out repose by trying to convince you that you do no need to try or, perhaps, that you need leave to room. In this state, one can practice Yoga by stilling the changing states of the mind and deny the monkey’s attempt at exerting its control. You may be struggling, but you don’t need to be suffering.

By cultivating control over the mind in a Bikram class, one can begin to cultivate this type of control outside of the hot room as well! A practitioner will begin to understand that the discomfort found in a 90-minute hot yoga class is not that unlike the discomfort found in day-to-day living. Ultimately, we realize that we do not have control over the myriad of factors that contribute to our suffering; the room is hot, the room is humid… so what? Just present your best effort.

Whether big or small wye, Yoga is all about taking control and making change. Whether one is practicing for the purpose of just changing how their physical form functions or if one is trying to reshape the may that they think and operate, Yoga can provide the means to accomplish their goals. Like most things in life, the start of something new can be tiresome, trying, and exasperating. Yoga teaches us that this is okay and promises to its adherents that it becomes easier with practice and will lead us to perfection.